Inventors Investing Inventively

Where did inventors put their money during the financial revolution?

It’s been quite a few months since my last newsletter. Mainly that time’s been spent teaching, but also working in archives and collecting data for my current projects on the origins of Britain’s industrial revolution. I’ve also been writing the proposal and first chapters for my next book Ruthless, that I’m delighted to say is now under contract with Yale for a 2025 release. I’ll be writing that over the coming year and sharing some of the research that’s going into it here. Thank you for reading!

Over the past few months I’ve been putting together a new dataset that details the investment portfolios of around 15,000 identifiable investors who were active between 1660 and 1720 (ie., after the Restoration and before the South Sea Bubble and Bubble Act).

There’s a lot to dig into within the data, but one of the first things that has jumped out is the presence of “inventors” (people named on patents granted during this period - sometimes a person who “owned” or invested in an invention rather than the actual “inventor”) as investors in all manner of other opportunities that opened up for budding capitalists during this period.

Big questions remain about the relationship between scientific, financial and industrial “revolutions”, and these inventor-investors are a group that I think help show the importance of links that bound together Britain’s economic system. First and foremost, we can see here already how different sectors of the economy benefited from a constant loop of cross-investment, cross-fertilisation of ideas, and the consequent development of goods and practices that benefited multiple sectors simultaneously.

For this post, I’m focusing in on the 277 inventors that were named on patents granted by the British state between 1680 and 1720. It’s an eclectic group, with landowners, merchants, clothiers, watchmakers, ship captains, engineers, miners, chemists, surgeons and the odd clergyman all present. They are all men (although one patent does note that the actual inventor - Sybilla Masters - was the wife of the patentee) and most would have held at least a middling social status in order to access the networks necessary for petitioning for their patent, a slow and sometimes expensive process. Their inventions, it must be stressed, were not universally useful or profitable, although some were important technological breakthroughs that contributed to the growing productivity of Britain’s economy over the following century.

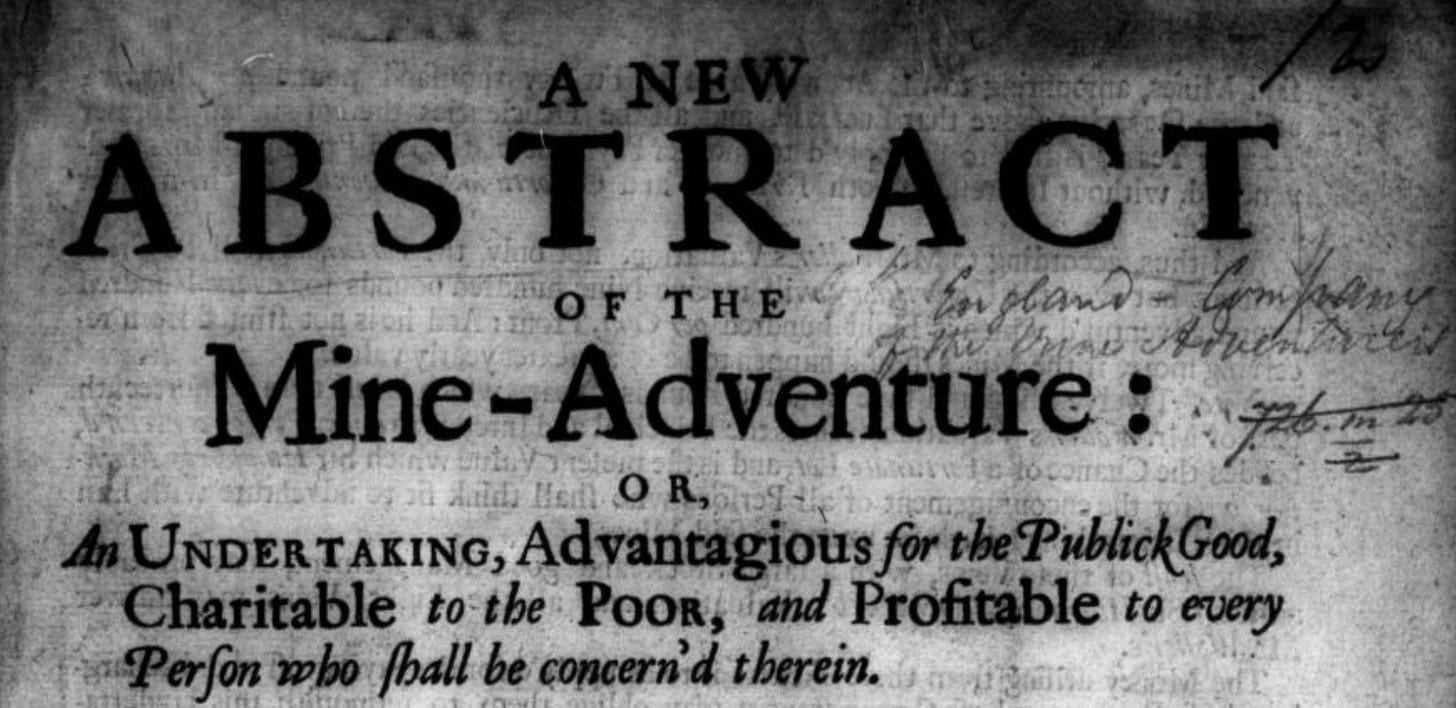

The inventions, like their inventors, were also pretty eclectic and related to an array of different sectors. Inventors were most active in the textiles sector, with sixty-patents granted that sought to improve what was both Britain’s largest manufacturing sector and the bedrock of it’s international trading success. This was closely followed by the fifty-nine inventions patented for Britain’s hugely important shipping industry. Patents related to heavy industry were also popular, with twenty-seven granted for in metallurgy, twenty-four in mining, and thirty for machinery with more general applications. Other prominent sectors included chemicals, with twenty-four patents, and agriculture, that was the focus of twenty-seven. A handful of patents in areas like weaponry (such as the Puckle Gun below, from 1718), transportation, pottery, utilities and building materials made up the rest.

However, while I will come back and write about those inventions and their repercussions some point in the future, for today I want to focus not on what inventors invented, but rather how this particular group of individuals engaged with the wider economy through their personal investment portfolios. Were inventors part of the expanding financial world that was taking place at the same time? If so, did they invest differently to other people? Did their inventions and financial interests align? Why is it important that financial and scientific (or perhaps mechanical) revolutions took place at the same time?

First off, yes, inventors certainly took part in the opportunities offered by the financial revolution. Among those 277 named inventors, sixty-eight were also investors. That might not seem like a lot, but at almost 25% it’s is actually a remarkably high proportion of inventors who invested when you put that number into context.

In total, approximately 20,000 people invested in the array of opportunities that became available during the febrile investment atmosphere between 1680 and 1720 (before the bubble burst and joint-stock corporation fell out of favour). Considering the appearance of new investment avenues, notably related to finance with the launch of the Bank of England, Million Bank and National Land-Bank, among others, the growth of active investors is not surprising, and it is certainly indicative of a growing pool of accessible capital that could be drawn on by firms.

That being said, the population of England was about 5,200,000 in 1700, so the investing public was only a very small part of the whole. Only around 0.38% of England’s total population were investors, meaning inventors were certainly much more likely than the “average Englishman” to take part.

In London, where the population had rapidly grown to around 575,000 by this point, investors were more common, but even here and in the wider south-east they were still a rare breed. Even had every investor been a Londoner that would still only represent a 3.48% investment rate among the city’s population.

There are a couple of important things to flag here. First, and most importantly, is the fairly limited access to investment for many people in Britain - if you weren’t in or near London, didn’t have capital to spare, and weren’t hooked up to existing investment networks then you were going to struggle to get involved. Not surprisingly, similar geographies and networks also facilitated the ability to obtain patents.

Inventors, though, certainly punched above their weight in terms of investment involvement. However, they weren’t the most active sub-set of the investing population. Perhaps inevitably, merchants were more likely to invest, especially in trade-related corporations like the East India Company or Royal African Company. For instance, among the merchants who were trading to the Mediterranean during this period, among the most profitable of trades, about 30% also invested in stocks at home. For the smaller Portugal merchant lobby, whose access via Lisbon to Brazil’s booming gold mining industry gave them quite the advantage, the number investing elsewhere too was over 71%.

Merchants, of course, had built many of the very corporate structures that were at the heart of the financial revolution, and their high level of participation is no surprise. A more useful comparison to inventors can probably found in groups that lacked this link, but who were still mostly wealthy and well-connected, and has some interest in new knowledge. For example, the Royal Society, that had been founded in 1660 to promote scientific discovery, saw 12% of its fellows invest during this period. For a more niche but more active group, we can find among the members of the Royal College of Surgeons who set up a free dispensary for medicine in 1704, 45% were also investors. If we take these as representative of Britain’s growing array of learned societies and “scientifically-minded” groups, they fit well alongside inventors as part of a new and engaged group that helped bridge the gaps between theoretical learning, practical science, and business opportunities.

That being said, the high proportion of inventors investing does suggest a higher level of investment to even some comparable groups. This can be explained by inventors inevitable interest in potential for profit and the possibility of making a real world impact with their new machines, processes or ideas. But, it also leads to another questions - did inventors invest inventively? Were they able to apply a unique perspective to engage differently with the investment opportunities available? Or did their engagement with the financial revolution simply mirror the involvement of the wider population?

So where did inventors invest? At a first glace, their portfolios look very similar to many other investors. Financial stocks were popular, and the National Land Bank attracted fifteen inventors to part with their cash, thirteen more invested in the Million Bank, and another eleven in the Bank of England. These were, in principle at least, relatively low risk investments that provided predictable returns, as well as being marketed as a key opportunity for investors to help their state and win the current war with France!

More risky and unpredictable, but potentially highly profitable opportunities across Britain’s emerging trading and colonial empire were also very popular investments for inventors. Nineteen invested in the East India Company that largely monopolised England’s trade with Asia, and nineteen invested in the South Sea Company to take advantage of a new treaty allowing English slave-traders to operate in the Spanish empire (a further three invested in the Royal African Company and four were part-owners of private slave-trading vessels, all profiting from the transportation of enslaved African people to Britain’s Caribbean colonies).

In these investments, inventors did indeed shadow the wider investing population; these five opportunities were the most popular for Britain’s total investing population too.

However, shifting focus away from the general popularity of these major investment opportunities towards the potential impact of inventors on particular organisations reveals a very different picture. In these massive, highly popular investments, inventors only represented between 1% and 2% of all investors in any of these organisations.

That perspective changes dramatically when we look at some of the less common investments that were available. Despite their small numbers, inventors made up 14% of the total investors in the Hollow Sword Company, 10% in the Tapestry Making Company, 11% in the Company for Making Lead with Pit Coal, and 13% in the Company Digging and Working Mines. In these much smaller companies, all of which lacked long tails of speculative investors, inventors were much more common. They are also where we can see the clearest links between inventors, their inventions, and the businesses where they put their capital on the line.

Why was that? At first glance there’s not always a clear link between inventor’s inventions and the sectors they invested in. Inventors who obtained patents in any one sector were almost identically likely to have invested as inventors active in another area. Despite having probably the weakest link to the investment opportunities available, 26% of inventors with patents related to agriculture were also investors - the highest proportion of investing inventors by sector. It wasn’t much higher than the rate of those with interests in any other field though (building 24%; chemicals 20%; maritime 19%; machinery 23%; metallurgy 22%; military 25%; mining 21%; textiles 25%).

It seems likely, then, that Dr Charles Morton’s patent for an “engine for beating ores, hemp and flax” had very little to do with his investments in the Bank of England, National Land Bank or Royal Exchange Assurance. Similarly, Ralph Marshall’s patent for “making spinnall yarn by ways never practiced in England” (because he’d just stolen the technique from Germany!) lacked a clear link to his ongoing investment in the East India Company. Inventing might have increased the propensity to invest, but it was hardly the case that inventors in general had a unique understanding or connection to specific investments. Instead, like many more well off people in Britain, they were well-connected, active in the right social networks, and simply more able to take advantages of investment opportunities available.

That being said, there are some much clearer links too. For instance, it’s not hard to imagine that his experience of investing in long voyages to the Ottoman Empire had inspired Thomas Maule before he patented a desalination technique specifically for “use both at land and at sea, and especially in long voyages, when many times great inconveniences, mortalities and sickness, whereby the benefit of the voyage are lost”. Similarly, Thomas Addison’s patent for an invention to “refine old iron into good and merchantable bar iron” made sense alongside investments in the Hollow Sword Blade Company and in mining.

Others, like John Booth, had only minimal connection between their invention, in this case a new method for winding silk, and their investments, in the National Land Bank and Charitable Corporation, but were strongly linked in their every day business activities, in this case as a London mercer.

A small number of investments stemmed specifically from inventions, and John Hodges patent for a method for “melting and refining lead ore in a reverberatory furnace using coal” was granted two years before the founding and his investment in a new company intended to do exactly that. In a similar vein, Ralph Lane’s participation in the Royal Lustring Company predated his patent for colouring cloth “woollen or silk, simple or compound, in figures, flowers, forestry, and landscapes” by only a couple of years. In each case, invention and investment were tightly bound together.

So did inventors invest inventively? As noted above, access to investment opportunities was probably roughly equivalent between inventors and members of the Royal Society, but the former were twice as likely to invest. This suggests something a little deeper than just different levels of market access. I think it’s fair to say that inventors were more engaged in the market and financial opportunities, while members of the learned society perhaps had less interest in the practical applications of their work. Indeed, inventors were more likely to have experience in business, whether in crafts, engineering or trade, and were much less likely to have obtained formal university education, let alone hold doctorates that were relatively common among the learned society crowd.

Examples like these, as well as overall patterns in the wider dataset considered above, give a tantalising glimpse into the important role that inventors played, both as part of the wider investing public but also as a unique sub-set. For some inventors, access to financial investments or to foreign trade were a means to ensure their financial security or to seek higher returns than their specialised fields might provide. For some specialist ventures, especially related to mining, metallurgy and textiles, inventors were a source of capital and expertise, and helped tie some emerging industries into wider financial markets. But perhaps most importantly of all, these links helped generate networks between capital, business, science and trade that contributed to ongoing cycles of innovation and investment that would underpin Britain’s transformative economic development over the coming century.

Note: The dataset that this post draws on is still being developed. However, later this year when the project finishes it will be deposited in the UK Data Archive. When that’s done I will try to remember to come back, repost this, and provide a link for other researchers.